What's Made Milwaukee Famous,

(has made a loser out of me)

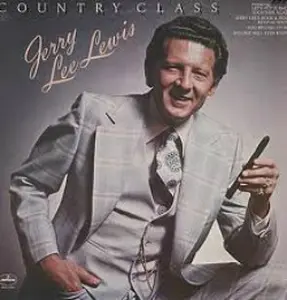

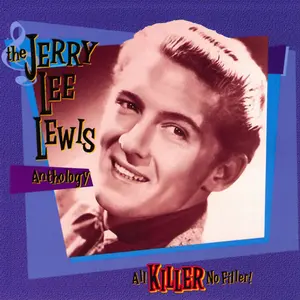

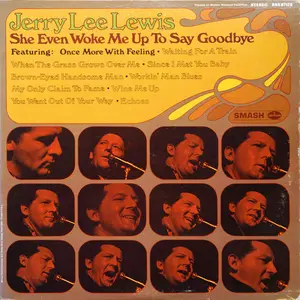

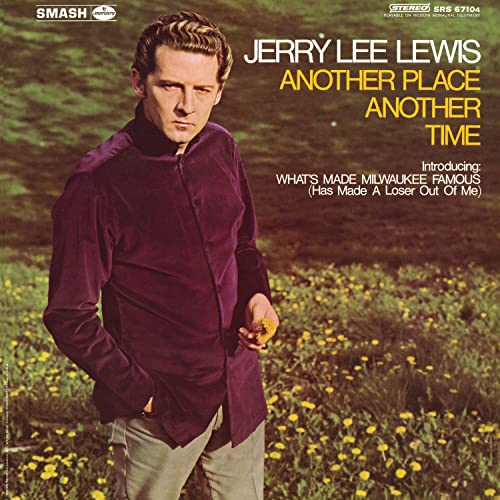

"What's Made Milwaukee Famous" is a reference to a famous beer slogan and features a #2 song from 1968 by the one and only, Jerry Lee Lewis.

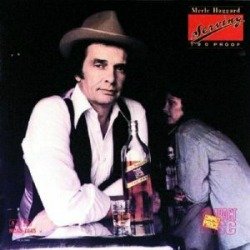

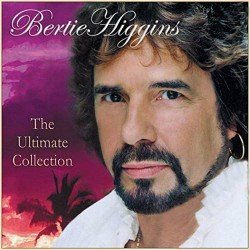

The song was released off the Album "Another Place, Another Time." The album was also a big hit and charted in at #3.

Another single off the album with the same name as the album title was released and rose to #4 on billboard's Country chart, proving just how popular this album really was. Another reason Jerry Lee Lewis had a country style better than 90% of Nashville's best.

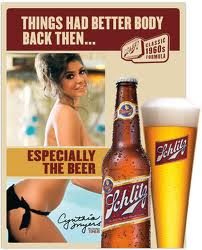

The Lyrics for this song was written by Glenn Sutton and the title is a reference to a Milwaukee Schlitz beer slogan, "Schlitz - The BEER that made Milwaukee famous."

What's Made Milwaukee Famous. The story behind the song.

In 1968, songwriter, Glenn Sutton was working as a staff producer at Columbia. A developing songwriter, he had also engaged a music publisher, Gallico Music Corporation, and was asked to come up with some material for Jerry Lee Lewis.

It was sometime during the mid-Sixties, Lewis, nicknamed "the Killer", had been persuaded by his producer, Jerry Kennedy, to switch styles over to the country sound to help jump start his career. Sutton had delayed writing material for Lewis and was put on the spot when he took a call from Al Gallico. A song was needed for a Lewis session the next day and Gallico wanted to know what he had.

Sutton had nothing prepared, but he didn't want to lose the work. He glanced at the papers on his desk. There was an ad for Schlitz, "the beer that made Milwaukee famous". Sutton later told a book author, "I just said to Al, it's a drinking song."

Sutton said he'd written a lot of drinking songs but never thought of using that Schlitz beer slogan. Their slogan made a great title for a country song. Sutton stayed up all night and "What's Made Milwaukee Famous (Has Made a Loser Out of Me)" was finished by daybreak.

How To Lose Your Wife Behind Those Swinging Doors.

He stood with his hand on the knob of their front door, the porch light painting him in a weak halo that made his promises look better than they were. She stood in the kitchen, dish towel wrung tight as if she could twist the night into a different shape. The clock above the stove ticked like a metronome set to their last argument.

“Just one,” he said, holding up a single finger. But the gesture was a habit, and so was the lie. Her eyes were tired, but not from sleep. “One turns into a song,” she said, “and a song turns into a round. You already know the ending. So do I.”

He offered a smile that meant to be charming and landed as an apology. “It’s been a long week down at the factory. Let me blow the dust off it. I’ll be back before the news.”

She looked down and then up, the way people do when they’re searching for the courage to lose. “Love and happiness can’t live behind those swinging doors,” she told him. Her voice didn’t crack. It wasn’t a threat. It was a verdict.

He nodded like the verdict fit him and stepped into the warm night that had nothing to do with the weather. Down at the end of the road, the billboard glowed with a cold bottle of Schlitz Beer and a promise. Everyone knew that beer. The famous one, the King. They didn’t even need to put the name on the board anymore. The bottle’s silhouette was enough to reach across the black sky and pull at a man’s thirst. He tried not to look. He looked anyway. The cold, inviting Schlitz bottle winked.

By the time he pushed through the bar’s swinging doors, the smoke and laughter had already recognized him. The doors swung like always, shuddering on their hinges, showing him a room that was exactly what he wanted it to be: dim enough to forget, bright enough to be seen.

“Look what the wind rolled in,” said Jerry behind the bar, wiping a glass like this was a western and not Friday night in a small town. “First one’s on the house. That famous stuff, right?”

“What else?” he said, and there it was, a cold Schlitz beaded with condensation like it had been sweating in anticipation of his arrival. The label’s gold caught the neon and played it back at him. He felt it before he tasted it: the knowing slide of ritual settling into his bones.

He told himself he’d drink slowly. He told himself he’d be a man about it. The first pull was a bite and a balm, bitter blooming into sweet, bubbles popping like distant applause. He checked the clock above the mirror and translated the time into something harmless. He could still be home before the weather.

The Jukebox Coughed Up An Old Heartbreaker.

He was standing ready to go when the jukebox kicked a gear and coughed up an old heartbreaker. A couple of fencepost cowboys at the end of the bar raised a cheer, and one of them, a man with a jaw like a boot heel, slapped a twenty down.

“Another round for the whole damn room,” he said, “for the song that taught me what I deserved.”

It would have been rude to walk out then, rude to let a full bottle sweat alone. Besides, the song found a soft corner of his memory and sat down on it. He raised his glass, said something about old roads and new mistakes, and drank.

By the second, stories started. The one about the night he proposed, cheap ring and expensive hope. Everybody laughed in the right places. He was charming again. He had proof that he could be.

He checked his phone, saw a missed call, a short text: Come home. He typed, erasing three drafts of apology because they were too long for what he’d done and too short for what he owed. He put the phone face down and told himself he was about to leave.

He swiveled off the stool. The doors swung in his mind—a kind of warning, a kind of invitation. Then a hand clapped his shoulder, a stranger with the look of overtime in his pupils. “You headed out? Can’t go now,” the man said. “Hear that? That one saved my life once. Let me buy you a drink so it can save yours.”

He could have said no. That was the worst part: he could have said no at almost any point. He let the no drift to the floor like a napkin. He stayed for the chorus. He stayed for the clink of glass. He stayed because the famous beer made everything feel like the high end of a true story.

Round by round, the room softened. The faces became friendlier, the edges of his worries rounded off like stones worn by a river he’d convinced himself he was just visiting. He got up to go again, and the bartender slid another bottle his way with the grace of a dealer laying down a winning card.

“For the road,” Jerry said.

He almost laughed. “That’s exactly the problem,” he told him, but he took the beer anyway, as if naming the problem counted for solving it.

When the jukebox stumbled into a dance number, a woman with mascara like war paint grabbed his hand and spun him into the small square of floor. He didn’t dance, not really, but his feet remembered a version of him that had once danced with his wife in their living room, pizza box on the coffee table, the world far, quiet, and forgiving. He thought about that, and then thought about how thinking about that felt like a punishment he could postpone. He smiled at the woman and let the song pull him along.

He was leaving when the old man from the corner, the one who drank from a glass that looked like it had been his since 1974, raised his voice. “Hey,” the old man said, “you remind me of my boy. He left town one day and forgot to come back. Have one with me so I can pretend he finally did.”

He took the seat. The old man’s hands shook pouring the pour, but his eyes were steady with their own unfixable thing. They talked about weather and tractors and wives like they were all the same machine, complicated and prone to failure if you didn’t listen. He lied and said he listened. The old man nodded like that was the best he’d heard all night.

The clock climbed through numbers the way water climbs a sinking boat.

When he finally did push through the swinging doors, the night had cooled into something clean and disinterested. The billboard with the Schlitz Beer Bottle still glowed. It looked tired now, or maybe he was seeing it without the bar’s forgiveness. He drove slowly, as if speed had ever been the problem.

The Porch Light's On, But Nobody's Home!

Their porch light was still on, but the house behind it felt evacuated. He stepped inside, and the air didn’t move to meet him. A quiet place can feel like a witness. On the hallway table, there was a rectangle of dust where a frame used to sit. The picture—she in her blue dress, he in his better self—was gone. The closet door hung open like a mouth about to say goodbye.

There was a note, but it didn’t need to be read. He read it anyway. It wasn’t long. It was the kind of letter written by someone who’s already said the words to themselves so many times that writing them down is just administrative.

She told him she’d asked him not to go. She told him she’d tried gentle. She told him, once again, “Love and happiness can’t live behind those swinging doors.” It didn’t sound angry, because it wasn’t. It sounded like a fact no one could argue with anymore.

He sat on the bottom stair and let the note hang from his fingers. The kitchen clock ticked. He had made his choices in tiny sips, and now he was drinking the whole consequence. He wanted to pick up his phone and dial and dial until her name answered, but he’d already used up the part where his wanting mattered.

He thought of the famous beer label and the way it caught the light like it was winning. He thought about how easy it had been to let the night stack its reasons between him and the door, to let the songs and the rounds and the thousand small kindnesses of strangers add up to a big unkindness to the only person who kept a chair open for him at their table.

He realized last what had been first all along. When he returned home, she was gone. He realizes now he’s to blame, but it’s too late, as the beer has made a loser out of him.

He stood, walked into the kitchen, opened the fridge just to close it again. Bottles knocked against each other with the polite music of a mistake you’re not ready to stop making. He turned off the porch light. Outside, somewhere past the trees, the highway hummed. In town, the swinging doors would be settling, creaking into the silence that comes after a room has emptied itself of excuses.

He leaned against the counter and waited for the first morning he’d have to meet without her. No jukebox. No rounds. Just the long and private work of learning how to walk past the Schlitz billboard with the without bowing to it. He stared at the blank space on the table where the framed photo had been. It was an honest space, at least. A starting line scratched into dust.

It All Came Down To The Title Of The Song.

The song is about a man, who's wife begs him not to go to the bar. He goes anyway and every time he starts to leave, another song is played and someone buys another round.

She told him "Love and happiness can't live behind those swinging doors" and when he returns home she's gone.

It all came down to the title of the song, What Made Milwaukee Famous (Schlitz Beer) made a Loser out of him.

Sutton is also well known for his personal and professional association with Lynn Anderson, his wife from 1968 to 1977. He produced many of her hit recordings, including her signature-mega hit "(I Never Promised You a) Rose Garden".

The album, by the same name as the single, reached number one in 16 countries around the globe and was the biggest selling album by a female country artist from 1971 until 1997.

Glenn Sutton died in April, 2007. He was 69.

In addition to being the home of Harley Davidson and where the TV show Happy Days was set, Milwaukee is the world's beer capital and has at one time or another had four major breweries based there: Blatz, Pabst and Miller, but it was the fourth Company, the Joseph Schlitz Brewing Company that came up with the slogan, "The beer that made Milwaukee Famous."

Enjoy another great country cheating song by Jerry Lee Lewis...

What's Made Milwaukee Famous (Has made a loser out of me)

Recorded by: Jerry Lee Lewis

Written by: Glen Sutton

From the 1968 Album "Another Place, Another Time"

It's Late and she's waiting

And I know I should go home

But every time I start to leave

They play another song

Then someone buys another round

And wherever drinks are free

What's Made Milwaukee Famous

Has made a loser out of me

Baby's begged me not to go

So many times before

She said love and happiness

Just can't live behind those swinging doors

Now she's gone and I'm to blame

Too late...I finally see

What's Made Milwaukee Famous

Has made a loser out of me

Baby's begged me not to go

So many times before

She said love and happiness

Just can't live behind those swinging doors

Now she's gone and I'm to blame

Too late...I finally see

What's Made Milwaukee Famous

Has made a loser out of me

What's Made Milwaukee Famous

Has made a loser out of me

Golden Oldies - Follow These Links For A Fun Trip Down Memory Lane.

Fifties Doo-Wop page - More Links To Your Classic Street Corner Symphonies.

Check Out Our Favorite Remakes Of Original Songs.

How About those Cars of Dreams We Grew Up With.

Return to Jerry Lee Lewis Main Page